Известия РАН. Серия географическая, 2022, T. 86, № 5, стр. 687-696

The preservation of the ethnic identity of new minorities in the Republic of Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

I. Medar-Tanjga a, *, D. Delic a, **

a University of Banja-Luka

Banja-Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

* E-mail: irena.medar-tanjga@pmf.unibl.org

** E-mail: dragica.delic@pmf.unibl.org

Поступила в редакцию 4.04.2020

После доработки 21.06.2022

Принята к публикации 12.07.2022

- EDN: SBIITS

- DOI: 10.31857/S2587556622050089

Аннотация

Political-geographic processes in the former Yugoslavia region have led to the creation of new political-territorial communities. The nationalities of Yugoslavia who have lived in the same country nowadays are living in Diaspora. Thus Montenegrins, Macedonians, and Slovenians in the Republic of Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina) from constituents have become new national minorities. The subject of the research is the position of the new minorities in the Republic of Srpska after the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia. Data on their number and territorial distribution are obtained by analyzing the last census of the population in the Republic of Srpska in 2013. It is also necessary to point to the relationship between the Republic of Srpska and the new minorities, as well as to the relations of the new minorities with their parent states. It is necessary to explore how these minority groups in the Republic of Srpska seek to preserve their ethnic identity and cultural heritage. Studying the Montenegrin, Macedonian and Slovenian associations, the history of their presence, and their association’s programs would reveal ways of preserving ethnic identity and elements of cultural heritage. There is a social, political, and scientific need to address this issue critically, to point to the status of new minorities in the Republic of Srpska, the possibility of their existence as well as the preservation of ethnic identity and elements of cultural heritage.

INTRODUCTION

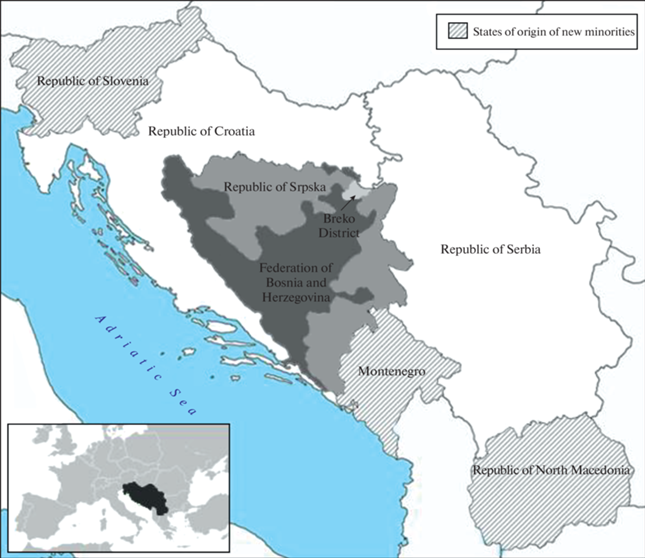

Within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (SRB&H), compared to other republics, had the most heterogeneous ethnic composition. In addition to national minorities, it was home to members of constituent nationalities that is originating from other republics of the mutual state. The disintegration of the SFRY led to numerous geopolitical processes that have directly affected the ethnic composition, number, spatial dispersion, and status of members of constituent nationalities and national minorities. With the formation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) as an independent state, administratively divided into two entities (Republic of Srpska—RS and Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina—FB&H) as well as Brcko District (Fig. 1), the number of constituent nationalities is reduced to Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks, while other constituent nationalities, Montenegrins, Macedonians and Slovenians, receive the status of national minorities. In the shadow of the three constituent nationalities in B&H and new minorities, there are also 14 other national minorities: Albanians, Czechs, Italians, Jews, Hungarians, Germans, Poles, Roma, Romanians, Russians, Ruthenians, Slovaks, Turks and Ukrainians11.

Law on the Protection of the Rights of Members of National Minorities of B&H, adopted in 2003 and amended in 2005 and 200822, relies on legal acts, including the most significant provisions of the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (1995), signed and ratified in 2000. The law prescribes several rights that the B&H authorities should guarantee to the minorities, including the right to use their language, and information, furthermore economic and social rights, and participation in authorities. Following the principles established in the B&H Law on Minorities, the Entities enacted their laws on minorities whose provisions prescribe the rights of minorities in the same way. The Law on the Protection of the Rights of National Minorities was adopted in 200433 and the Law on the Protection of the Rights of National Minorities of the Federation of B&H was adopted in 200844.

In 2008, the Parliamentary Assembly of B&H established the Council of National Minorities of the B&H as a special advisory body, which provides opinions, advice and suggestions to the Parliamentary Assembly of B&H on all issues related to the rights, positions and interests of national minorities in B&H. This advisory body consists of one representative of each legally recognized national minority. The Council of National Minorities may delegate its experts to participate in the work of constitutional committees and the Joint Commission on Human Rights, the rights of the child, young people, immigrants, refugees, asylum, and ethics of the Parliamentary Assembly of B&H when they discuss the rights, position and interests of national minorities.

In 2007, the National Assembly of the RS established the Council of National Minorities of the RS as a special advisory body composed of members of national minorities proposed by the Federation of National Minorities of the RS. The Council of National Minorities of the RS gives opinions and proposals to the National Assembly on all issues concerning the rights, position, and interests of national minorities in the RS.

The study examines the position of Montenegrins, Macedonians, and Slovenians—the new minorities in the RS and the possibility of preserving their ethnic identities and cultural heritage. The analysis of the 2013 census will provide data on their number and territorial dispersion. The analysis of the 2013 census will provide data on their number and territorial dispersion. In the context of preserving the identity, the attitude of the Republic of Srpska and the attitude of the motherland countries towards them is being investigated. How these minorities seek to preserve their identity and cultural heritage will be monitored through an analysis of the origins, functioning, action programs and funding of their associations in the Republic of Srpska.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Basic data on the number, ethnic composition and territorial distribution of the population of B&H in the SFRY can be found in publications issued after the census of 1948−1991 (Stanovništvo …, 1995). With the formation of the B&H, censuses are published at the entity level.55 RS population data have also been published in papers dealing with this issue, but they are based mainly on the analysis of the structures and territorial distribution of the three constituent nationalities, while members of national minorities and other ethnic minority groups were treated through the category of “others” (Зекановић, 2011; Маринковић and Мајић, 2018; Медар, 2008; Bell, 2018; Cvitković, 2017; Zekanović and Gnjato, 2018). The literature on national minorities in B&H and RS observes their number and the legal systems that protect their rights, as well as the results and conclusions that coincide with the results presented in this paper (Katz, 2017; Kukić, 2001; Lalić and Francuz, 2016; Slavuljica, 2010).

The study of minority communities, especially in highly heterogeneous states, implies an insight into their identity characteristics. An overview of different theories offers a whole range of definitions of the concept of identity (Calhoun, 1994; Lash and Jonathan, 1991; Moya and Hames-Grasía, 2000). In the context of this paper, minority groups, as cultural collectives stand out based on the most important ethnic characteristics: language, religion, tradition and culture (Friedman, 1994; Glazer and Moynihan, 1975; Isajiw, 1974; Jenkins, 1997; Liebkind, 1989; Smith, 1991). In B&H, this problem is complex because members of the three constituent nationalities belong to different religions: Serbs to Orthodoxy, Croats to Catholicism, and Bosniaks to Islam. In addition, they declared three separate languages derived from the common Serbo-Croatian: Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian. Members of the new minorities also have complex identity characteristics: Montenegrins—Serbian and Montenegrin mother language and belonging to Orthodoxy, Macedonians—Macedonian mother language and belonging to Orthodoxy and Slovenians—Slovenian mother language and belonging to Catholicism. As in the case of statistics, identity characteristics were studied for the three constituent nationalities (Попадьева, 2021; Bringa, 1993; Cvitković, 2017; Tošović and Wonisch, 2010) and studies of national minorities were lacking.

The status of national minorities of RS is observed at the level of state and entity institutions and bodies dealing with these issues. Current legal acts and activities organized to promote the rights, positions and interests of national minorities have been analyzed. Interviews with presidents of associations of Montenegrins, Macedonians and Slovenians provided information on the number of association’s members, activities they conduct to preserve language, tradition and culture, the way of financing the activities, their relationship with their parent state, relations with institutions and bodies in B&H and RS, as well as their perception of the possibility of improving their position in the RS.

METHODS

The methodological approach and research methods are tailored to the tasks and the research goal. Considering the complexity of the problem, the interdisciplinary approach is dominant. To a full extent, methods of analysis, synthesis, comparison, historical, cartographic, demographic method, and inductive and deductive research methods will be used. Based on the historical, geopolitical, demographic, cultural and legal facts, the position of the new minorities in the RS will be highlighted. Field research and cabinetwork are the basic techniques applied in the methodological process.

ORIGIN OF THE NEW MINORITIES

The origin of the new minorities is related to the presence of their members in the RS since the formation of the first common states in southeastern Europe.

Encouraged by Turkish conquest from the south, the Montenegrin people were forced to migrate north of the indigenous territory they inhabited. With the formation of the first common state of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians in 1918, Montenegrins settled on the territory of Herzegovina (southern part of RS), which forms the border area towards Montenegro. Most Montenegrins came to B&H during the time of the former SFRY in search of education, jobs, and better living conditions.

The presence of Macedonians in the territory of RS is a consequence of economic migration at the beginning of the 20th century. A larger wave of immigration was recorded during the Second World War and during the time of the former SFRY. They mostly inhabited major cities: Banja Luka, Brcko, Sarajevo, Bijeljina, Doboj, Derventa, Prijedor.

The migration of Slovenians to the territory of RS had an economic character. Numerous untapped natural resources were the target of occasional labour migration as early as the middle 19th century. With the annexation of B&H by the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the planned and permanent settlement of Slovenians in the territory of B&H, primarily to the main industrial centres, begins. The second major wave of immigration occurred with the creation of the first mutual state of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians in 1918, when part of the Slovenian territory belonged to Italy, causing emigration. During the Second World War, the number of Slovenians in B&H decreased, which changes after the end of the war. Experts from many profiles come to B&H and participate in the raising of businesses and higher education institutions.

Since these are nationalities whose present-day states, together with the territory of the RS, belonged to the common state of the SFRY, the process of immigration and permanent settlement in the RS has been facilitated (Fig. 1).

Numerous contemporary geopolitical processes, triggered by the disintegration of the mutual state at the end of the 20th century, have caused complex socio-geographical changes throughout the region, including the RS. The changes are reflected primarily through migration, which has led to changes in the number, and spatial distribution of the population, but also to changes in the status of minority nationalities in all the newly created states. In the territory of B&H and RS, the mentioned processes were most intensively covered by the members of the new minorities.

NUMBER AND TERRITORIAL DISTRIBUTION

Given that the censuses served as a political instrument and that some nationalities declared themselves in different ways through the censuses, it is difficult to establish the exact number of constituent nationalities, that is, today’s emerging national minorities. It is important to emphasize that in the former mutual state, ethnicity began to express itself freely in the post-war censuses (Mrdjen, 2002). For this reason, the change in the total number of members of the new minorities will be analyzed for the period 1948 to 2013 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of new minorities in B&H, 1948–2013 censuses, people

| Minority | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegrins | 3094 | 7336 | 12 828 | 13 021 | 14 114 | 10 071 | 1843 |

| Macedonians | 675 | 1884 | 2391 | 1773 | 1892 | 1596 | 667 |

| Slovenians | 4338 | 6300 | 5939 | 4053 | 2755 | 2190 | 911 |

| Total population | 2 565 277 | 2 847 790 | 3 277 948 | 3 746 111 | 4 124 256 | 4 377 033 | 3 473 078 |

Compiled from: Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова у Босни и Херцеговини, Етничка/национална припадност, вјероисповјест и матерњи језик. Сарајево: Агенција за статистику Босне и Херцеговине, 2019; Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова у Републици Српској 2013. године. Бања Лука: Републички завод за статистику Републике Српске, 2017; (Stanovništvo …, 1995).

In the first post-war census of 1948 Slovenians (0.17%) are the most numerous with Montenegrins (0.12%) and Macedonians (0.03%). As early as the next census in 1953, this relationship changed and Montenegrins with 0.26% participation became the most numerous. Slovenians participated with 0.22%, Macedonians with 0.07% and such a relationship has remained to this day. This can be explained by the fact that Montenegro, unlike the Republic of North Macedonia and the Republic of Slovenia, borders B&H, and for that reason, the presence of Montenegrins is greater. According to the 1961 census, Montenegrins are the most numerous (0.39%). They were followed by Slovenians with 0.18%, then Macedonians with 0.07%. The number and percentage of Slovenians from these censuses will continue to decline until today. The reason for this lies in the fact that Slovenia was more developed and desirable for life both as part of a common state and as an independent state. In 1971 number of Slovenians (0.11%) and Macedonians (0.05%) declined slightly, while the absolute number of Montenegrins continued to grow, although the participation in the total number decreased (0.35%). This decline is a potential consequence of the revised 1971 census methodology. Specifically, this census introduces the category “regional affiliation” as well as the possibility that the population does not declare nationally. The 1981 census shows an increase in the absolute number of Montenegrins and Macedonians, although their participation in the total population of B&H decreased (Montenegrins 0.34%, Macedonians 0.05%). The number of Slovenians is declining, as is their participation (0.07%).

An intense decline in the number of all three nationalities was observed in 1991 when the disintegration of the mutual state of the SFRJ began. Slovenia held a referendum on independence in 1990, Croatia and Macedonia in 1991, and B&H in 1992 (Begić, 1997). Of the total population of B&H, Montenegrins participated with 0.23%, Slovenians with 0.05%, and Macedonians with 0.04%. This decrease can be explained by the processes of assimilation, as well as by declaring the nationality of one of the three largest groups in B&H (Serbs, Croats, and Muslims) in the light of national propaganda caused by current geopolitical events. This mostly happened in the case of mixed marriages (Медар, 2008).

Although it did not formally exist as an entity at the time, the area of the RS in 1991 was populated by members of these national minorities in much more considerable numbers. By identifying the five cities in the RS where these nationalities were most represented (Table 2), it can be concluded that their population is represented in a large proportion by the total number of Montenegrins, Macedonians, and Slovenians at the level of B&H. Thus, in these cities, 23.18% of Montenegrins, 21.17% of Macedonians and 24.65% of Slovenians are inhabited by their population at the level of B&H. National minorities in these cities made up a small proportion of the total population of B&H (Montenegrins 0.05%, Macedonians 0.01%, and Slovenians 0.01%). It can be concluded that the majority of the members of these national minorities lived in the FB&H.

Table 2.

Тhe cities with the largest number of new minorities, 1991 and 2013 censuses, people

| Montenegrins | Macedonians | Slovenians | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 2013 | 1991 | 2013 | 1991 | 2013 | ||||||

| Trebinje | 751 | Banja Luka | 323 | Banja Luka | 186 | Banja Luka | 124 | Banja Luka | 430 | Banja Luka | 224 |

| Banja Luka | 567 | Trebinje | 214 | Bijeljina | 66 | Prnjavor | 36 | Gradiška | 28 | Prijedor | 65 |

| Bileća | 345 | Foča | 75 | Doboj | 32 | Bijeljina | 31 | Laktaši | 40 | Laktaši | 46 |

| Foča | 542 | Bileća | 53 | Prijedor | 29 | Laktaši | 16 | Doboj | 21 | Prnjavor | 20 |

| Doboj | 150 | Doboj | 48 | Trebinje | 25 | Doboj | 14 | Trebinje | 21 | Bijeljina | 20 |

| Total | 2355 | Total | 713 | Total | 338 | Total | 221 | Total | 540 | Total | 375 |

Compiled from: Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова у Босни и Херцеговини, Етничка/национална припадност, вјероисповјест и матерњи језик. Сарајево: Агенција за статистику Босне и Херцеговине, 2019; Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова у Републици Српској 2013. године. Бања Лука: Републички завод за статистику Републике Српске, 2017.

The disintegration processes in the former SFRY were marked by civil and ethnic-religious war, which within B&H lasted from March 1992 till December 1995 (Zekanović and Gnjato, 2018). War and so-called “War migrations” have left tragic consequences for the demographic situation in B&H. The first census was conducted in 2013 at the entity level (Table 3) under pressure from the domestic public and the international community (Cvitković, 2017).

Table 3.

Number of new national minorities in B&H and its parts, 2013 census, people

| Area | Montenegrins | Macedonians | Slovenians | Total population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS | 1116 | 341 | 504 | 1 170 342 |

| FB&H | 696 | 301 | 398 | 2 219 220 |

| Brcko District | 31 | 25 | 9 | 83 516 |

| B&H | 1843 | 667 | 911 | 3 473 078 |

Compiled from: Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова у Босни и Херцеговини, Етничка/национална припадност, вјероисповјест и матерњи језик. Сарајево: Агенција за статистику Босне и Херцеговине, 2019; Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова у Републици Српској 2013. Године. Бања Лука: Републички завод за статистику Републике Српске, 2017.

According to these data, Montenegrins are still the most numerous in B&H, with a share of 0.05% of the total population. In RS, their participation is twice as high and amounts to 0.10%. Slovenians make up 0.03% of the total population of B&H or 0.04% of the total population of RS. Macedonians participate in the total population of B&H with 0.02%, while their share in the RS population is 0.3%. Compared to the 1991 census, there is a clear decrease in the number of new minorities, both in B&H and in RS, which, along with assimilation, can be explained by the return to the countries of origin caused by the war in B&H. It is estimated that 70–75% of members of national minorities left their former residences during the war.

Considering the spatial distribution of the new minorities at the level of B&H, and within the entities, it is important to point out that Montenegrins, Macedonians, and Slovenians are more numerous in the RS than in the FB&H. The share of Montenegrins from the RS in the total number at the level of B&H is 61.58%, Macedonians 53.11% and Slovenians 55.87%. In RS, these new minorities make up 0.17% of the total population. The analysis of changes in the spatial dispersion of the members of the new minorities in the RS shows that in 1991 and 2013 they were the most represented in the development centres, that is, their distribution is uneven across the entire territory of RS (Table 2). A common feature of these new minorities is the concentration in Banja Luka. The spatial distribution of Montenegrins has remained unchanged since 1991, and they remain the most numerous in the cities: Banja Luka, Trebinje, Foča, Bileća, and Doboj. Their presence is accentuated in eastern Herzegovina, which represents the border area with Montenegro. Changes in spatial distribution occurred among Macedonians and Slovenians, and unlike in 1991, their numbers were preserved in the cities located in the North of the RS. Uneven oasis distribution of new minorities, with the greatest participation in RS development centres, significantly complicates the operation of institutions, mechanisms, and instruments for the protection of their rights, which in these conditions often comes down to local character.

CONTEMPORARY FACTORS OF IDENTITY PRESERVATION

With the formation of the state of B&H, members of the nationalities of the former Yugoslav republics who did not receive the status of constituent nationalities found themselves, not through their fault, in a very unenviable position. As new national minorities, they have formed various associations, mostly on ethnic basis.

Montenegrins in RS are organized into 6 associations (two in Banja Luka, two in Trebinje, one in Gradiška, and one in Doboj) which are not organized into an umbrella association. They are members of the Federation of National Minorities of the RS whose offices are used by associations from Banja Luka. The total number of Montenegrins in associations ranges between 300 and 400 members with a tendency to decline, and even with a tendency to shut down some associations. Associations do not cooperate, either at the local, entity, or state level. A regular activity calendar does not exist. The same language as well as the religion with the Serbs, as the constituent people of B&H, Montenegrins stated as an obstacle to preserving their cultural identity, which is reflected mainly through the organization of art exhibitions, literary evenings and theatre performances. Members of the association take part in the Annual Assembly of the Montenegrin Diaspora, held in Montenegro at the end of May, and in commemoration of national holidays (National Day of Montenegro—July 13) and other significant dates (Lučindan—date of death of the founder of modern Montenegro, Peter I Petrović Njegoš—October 31). The associations are financed by regular funds of local communities, yearly from EUR 250–500 for one association which is spent through projects. Furthermore, funds are received from the Ministry of Education and Culture RS but only if their project is approved through the competition for National Minority Projects. Representatives of Montenegrins emphasize the complicated administrative procedures as an obstacle to applying for the funds from the RS Government. There is no support from their parent state, and this fact, with modest finances by the state in which they now live, is singled out as a major defect in the functioning of the association. This causes the younger members to become less interested and the older people’s enthusiasm for preserving their cultural and national identity lessened.

Macedonians in RS have only one association registered in Banja Luka, with about 80 members, of which 30 participate in the activities of the association, and 5 of them are active. The representative of the association believes that this single association will also be extinguished since the members are mostly in mixed marriages, so their assimilation is inevitable. This process is also influenced by the similarity of the Macedonian and Serbian languages and the same religious affiliation. He also points out the fact that young people are not interested in engaging in the work of the association, because they have almost no benefit from it. This association does not have any cooperation with similar associations in the FB&H. Until 6–7 years ago, the association organized language classes, but this activity was discontinued due to the poor interest of the members. To preserve and promote culture, the association organizes exhibitions, lectures, and workshops on embroidery and painting. In addition, significant dates are celebrated each year in the association, such as the Blessed glory of Cyril and Methodius (May), the Independence Day of the Republic of North Macedonia (September 8), The Day of Uprising in the Republic of North Macedonia (October 10), The Day of Macedonians (the second half of December). The only permanent source of funding is a local community grant of EUR 750, which is paid out in two installments on a semi-annual basis for regular activities. They receive funding from the RS Government’s budget if they have successful projects in the Ministry of Education and Culture’s National Minority Competition. Although there is an Emigration Agency in the parent state without actual support.

Slovenians have two associations registered on the territory of RS: one in Banja Luka, which has about 1000 members, and the other in Prijedor with about 300 members. Members of these associations are not declining and they believe that it will remain so. The reason for this situation can be found in the fact that children of Slovenian citizens automatically gain Slovenian citizenship, and the Republic of Slovenia is attractive to the population of B&H because of the possibility of education and work in the European Union which the Republic of Slovenia is a member. These associations are members of the Federation of National Minorities of RS. Both associations have their premises received from their local municipalities. Slovenians are the only new minority in the territory of B&H which associations are part of the Federation of Slovenian Societies in B&H. The most important activities in the preservation of identity are the regular Slovenian language classes, which are held in ten groups twice a week for all interested members of society, as well as for other citizens. This activity, called “Supplementary Teaching of the Slovenian Language, Culture and Customs”, is funded by the Republic of Slovenia through the payment of work and accommodation for the teachers coming from the Republic of Slovenia. Children who attend these classes can visit Slovenia schools for 14–21 days to master the language more actively. The association from Banja Luka has a folklore and choir section, whose leaders are also funded by the parent state, as part of regular activity through the Office for Slovenians Worldwide in the Government of the Republic of Slovenia. All associations, if they have organized these activities, participate in joint manifestations at the level of B&H: meetings of pupils of supplementary classes (mother language), meetings of choirs, and meetings of folklore groups. The most important joint event “Slovenians Meet” is held every year in one of the cities of B&H in which the association exists. At the level of the region since 2014, a Quiz of Knowledge on Slovenian History, Culture and Customs has been organized, with the participation of members of associations, aged under 14, from the Republic of Serbia, the Republic of Croatia and B&H. Significant dates for Slovenians are also regularly celebrated: Presern’s Day (February 8), Slovenian Days in Slatina (last weekend in June), St. Martin’s Day (middle of November). In addition to these joint activities, both associations of Slovenians in the RS have dozens of activities organized to preserve their identity. The association from Banja Luka emphasizes the yearly publication of a bilingual book with texts by Slovenian and local writers. As Slovenians are known as passionate book readers, a quiz on reading books is organized, and successful members of this competition go to the Republic of Slovenia to receive the award. The same association publishes two newsletters annually: The Bulletin of the Slovenian Association of the RS “Triglav” and the school bulletin “This Is Us” in the Slovenian language. The associations are funded by the local community (association from Banja Luka receives around EUR 2500 annually) and through numerous projects under the Ministry of Education and Culture in the RS Government, the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the Ministry of Human Rights and Refugees in the Government of B&H. Slovenians have trained members for writing the project applications for local and state funds, as well as European Union funds where they can participate as partners. The support of the parent state in the case of the Slovenian minority is significant. In addition to financing the ongoing activities of all associations, the parent state participates in the co-financing of all projects of the associations. Support is also evident through the various forms of linking of institutions and societies from the Republic of Slovenia and the RS, of which is stated the connection of Slovenian Novo Mesto high schools with those of Banja Luka.

All minority associations participate in the activities of the Federation of National Minorities of the RS, through participation in the National Minorities Cultural Creativity Festival, and participation in some joint projects. One of the more interesting projects is the “Competition of Elementary School Pupils on Knowledge of National Minorities,” which has been implemented in various RS cities since 2015. The main objective of this project is to get to know the history, culture and customs of minority communities but among the children of constituent nationalities. The Federation of National Minorities of the RS publishes a Bulletin once a year in which all national minorities represent their activities.

Representatives to the Council of National Minorities of the RS are elected by agreement, usually from among members of associations. In the case of a Slovenian minority, the election of a representative to the Council of National Minorities of B&H is made by selecting a member from the Federation of Slovenian Societies in B&H. It is followed that representatives from the territory of RS and FB&H are alternately selected. Montenegrins and Macedonians replace their representatives on the same territorial principle, with the problem of selection because RS and FB&H associations do not cooperate. Often happens that the elected representative represents only one side. Members of all new minorities think that although they have an advisory character, these councils are completely irrelevant to their functioning since they exist only formally and practically do not deal with minority issues. They have the same attitude when it comes to national minority laws. In practice, they are just dead letters on the paper.

National minorities are almost “invisible” in the media. Public service Radio-Television of RS once a week broadcasts a TV show about national minorities “Little Europe” for half an hour and broadcasts a radio show “Roots” for one hour every other Saturday. This topic is covered by the Public Broadcasting Service of B&H through the topics of the radio show on minorities “Among Us About Us” which is broadcast once a week for 45 minutes. Presence in the media would contribute to the strengthening of minorities, and the promotion of their language and culture. In addition, intercultural communication would be ensured, minority identities would be promoted, and stereotypes and prejudices would be eliminated.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the former Yugoslavia, SRB&H had the most heterogeneous composition of the population, which is why it was a factor of stability of the entire state and bore the epithet “Yugoslavia in small.” In addition to Serbs, Croats and Muslims, the constituent nationalities were peoples originating from other republics of the common state—Macedonians, Montenegrins, and Slovenians. With the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the formation of B&H as an independent state, these three nationalities gained the status of national minorities. Problems related to minority issues have been resolved by the international community using international law to protect minorities found in the former Yugoslav states. Thus, in B&H, at the state and entity levels, legal acts were adopted and institutions were formed according to the standards of protection of minority rights. However, the level of exercised rights in practice is very low, especially in the areas of participation in public and political life, status issues, education and culture. Minority political participation has been reduced to the establishment of reserved minority seats at the local level and the formation of consultative bodies at the state and entity levels, as well as at certain lower levels of government. The main problem is to equalize the issue of minority participation in local government with political (party) representation.

Research has shown that the requirements of the law related to teaching in minority languages have not been applied anywhere in B&H. The teaching of languages of new minorities through additional, optional teaching has not been introduced by any school in RS. Only members of the Slovenian minority are interested to learn their mother language through extracurricular activities in associations exclusively with the support of the parent state. The introduction of languages in schools, the provision of textbooks and teaching materials, and the recruitment of qualified teachers are some of the measures that would enhance language learning, and thus strengthen the identity of national minorities, regardless of the support of their parent countries.

The analysis of the activities of minority associations has determined that they represent the most important form of preserving the identity and cultural heritage of these groups. The main problem is the lack of involvement of members of minorities in associations. Functioning and action programs are mostly the result of the personal engagement of the association’s leaders, and the crucial factor is modest funding, which is usually reduced to funds obtained through competitions for projects by local communities and the RS Ministry of Education and Culture. According to all the characteristics, the Slovenians stand out, who have the largest membership, an elaborated program of activities, but also significant support from the motherland in financing numerous activities.

The unenviable position is confirmed by the weak participation in the media space of the Public Service of the Radio-Television of RS. Increasing the visibility of national minorities in the media would be achieved by introducing specific programs for national minorities or by establishing a radio station intended for persons belonging to national minorities by public broadcasters.

Considering that the protection of the rights of national minorities is one of the cornerstones of the constitutional system of B&H and RS, strategic documents have been drawn up at both levels. Thus, at the state level in 2014, a Strategic Platform for solving issues of national minorities in B&H (Strateška …, 2014) was elaborated. At the RS level, the Strategy for the Promotion and Protection of Rights of National Minorities in RS for the period 2020–2024 (Стратегија …, 2019) has been adopted in 2020. The adoption of these documents aims to further improve the existing rights and status of persons belonging to national minorities in various fields (culture, education in their mother language, information, etc.), as well as the involvement of persons belonging to national minorities in the processes of creating public policies, through the realization of strategic and operational goals and establishing better and more efficient cooperation with the Government, bodies and institutions of B&H and RS.

In the end, it can be concluded that unless the real status of minorities is harmonized with legal acts, the territory of the former Yugoslavia will continue to emerge as an unstable area, filled with economic difficulties and crises, nationalism and xenophobia, which is an obstacle to a rational policy that would allow all emerging countries of the region to be introduced into a united Europe.

Список литературы

Зекановић И. Етнодемографске основе политичко-географског положаја Републике Српске. Бања Лука: Географско друштво Републике Српске, 2011. 221 с.

Маринковић Д., Мајић А. Становништво Републике Српске – демографски фактори и показатељи. Бања Лука: Универзитет у Бањој Луци, Природно-математички факултет, 2018. 342 с.

Медар И. Мјештовити бракови на подручју општине Бања Лука (1987–2000. године). Бања Лука: Географско друштво Републике Српске, 2008. 126 с.

Попадьева Т.И. Языковая политика как инструмент формирования гражданской идентичности: на примере Боснии и Герцеговины // Вестн. МГИМО-Университета. 2021. Т. 14. № 4. С. 91–106.

Стратегија за унапређивање и заштиту права припадника националних мањина у Републици Српској за период 2020–2024. Бања Лука: Министарство управе и локалне самоуправе Републике Српске, 2019.

Begić. K.I. Bosna i Hercegovina od Vanceove misije do Daytonskog mirovnog sporazuma. Sarajevo: Bosanska knjiga, 1997. 336 s.

Bell J. Dayton and the Political Rights of Minorities: Considering Constitutional Reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina after the Acceptance of its Membership Application to the European Union // J. on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe. 2018. Vol. 17. № 2. P. 17–46.

Bringa T.R. Nationality categories, national identification and identity formation in “multinational” Bosnia // Anthropology of East Europe Rev. 1993. Vol. 11. № 1–2. P. 80–89.

Cvitković I. (Ur.). Demografske i etničke promjene. Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, 2017. 160 s.

Ethnicity / Glazer N., Moynihan P.D. (Eds.). Massachusetts: Harvard Univ. Press, 1975. 512 p.

Friedman J. Cultural Identity and Global Process. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publ. Ltd, 1994. 270 p.

Isajiw W.W. Definitions of ethnicity // Ethnicity. 1974. Vol. 1. № 2. P. 111–124.

Jenkins R. Rethinking Ethnicity. London: SAGE Publ. Ltd, 1997. 197 p.

Katz V. The Position of National Minorities in Bosnia and Hercegovina before and after the Breakup of Jugoslavia // Studia Środkowoeuropejskie i Bałkanistyczne. 2017. Vol. 26. P. 193–204.

Kukić S. Položaj nacionalnih i vjerskih manjina u Bosni i Hercegovini // Politička misao: časopis za politologiju. 2001. Vol. 38 № 3. P. 122–137.

Lalić V., Francuz V. Ethnic minorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina – current state, discrimination and safety issues // Balkan Soc. Sci. Rev. 2016. Vol. 8. P. 153–179.

Modernity and Identity / Lash S. and Jonathan F. (Eds.). Oxford: Blackwell, 1991. 392 p.

Mrdjen S. Narodnost u popisima. Promjenjljiva i nestalna kategorija // Stanovništvo. 2002. Vol. 1. № 4. S. 77–104.

New identities in Europe: Immigrant ancestry and the ethnic identity of youth / Liebkind K. (Ed.). Vermont: Gower Publ. Company, 1989. 296 p.

Reclaiming identity / Moya M.L.P., Hames-Grasía R.M. (Eds.). Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 2000. 364 p.

Slavuljica N. Pravni okvir: Bosna i Hercegovina, u Manjine za manjine. Mikić Zeitoun M. i Jurlina P. Ur., Zagreb: Centar za mirovne studije, 2010. S. 120–132.

Smith D.A. National Identity. London: Penguin Books, 1991. 236 p.

Social Theory and the Politics of Identity / Calhoun C. (Ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1994. 364 p.

Stanovništvo Bosne i Hercegovine, narodnosni sastav po naseljima. Zagreb: Državni zavod za statitsiku Republike Hrvatske, 1995.

Strateška platforma za rješavanje pitanja nacionalnih manjima u Bosni i Hercegovini. Sarajevo: Ministarstvo za ljudska prava i izbjeglice Bosne i Hercegovine, 2014.

Tošović B., Wonisch A. (Ur.). Srpski pogledi na odnose između srpskog, hrvatskog i bošnjačkog jezika 1/2. Grac, Beograd: Institut für Slawistik der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Beogradska knjiga, 2010. 547 s.

Zekanović I., Gnjato R. Disintegration of the former SFR Yugoslavia and changes in the ethno-confessional structure of some cities of Bosnia and Herzegovina // RUDN J. of Economics. 2018. Vol. 26. № 4. P. 685–696.

Дополнительные материалы отсутствуют.

Инструменты

Известия РАН. Серия географическая